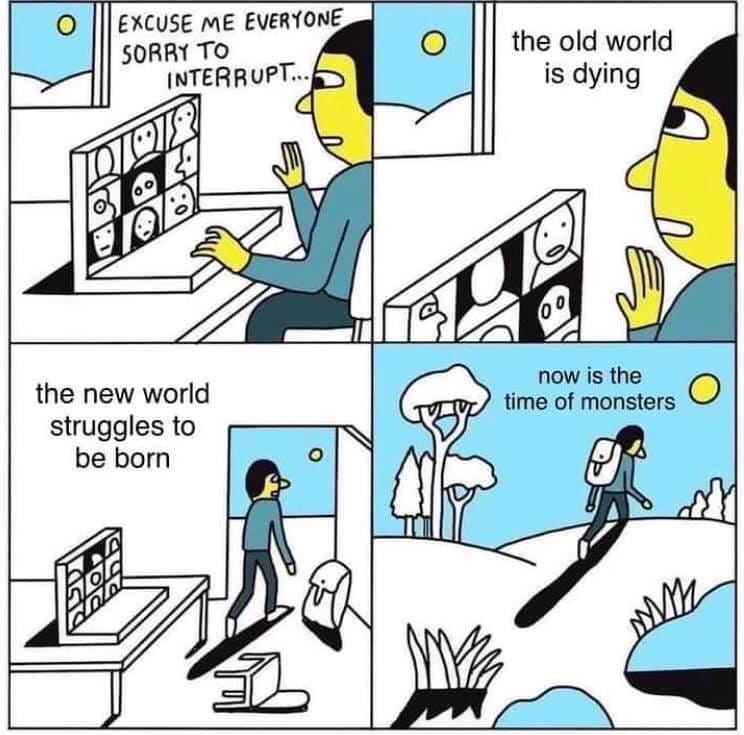

Here we are in another bitter interregnum, one that feels like a final nail in the coffin of a hopeful future. The earth burns, ‘Compromise’ at the expense of trans, disabled, or nonwhite people is discussed to maintain institutional civility, and every day is a barrage of worst case scenarios. Slavoj Žižek’s version of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks quote feels right, it is the time of monsters. It’s still debated what the fenomeni morbosi’ (lit. ‘morbid phenomena’ in Gramsci’s original Italian) refers to (fascism? Risky ultra-left movements?) As a monster researcher by trade, I appreciate Žižek’s invocation of the monstrous, because he’s right. In this cruel and crucial time, we must look hard at our monsters, which of course requires us to look at ourselves.

Rather than being an inevitability in every good story, the monster is a product of polarization and rupture. Monstrous characters are therefore system-breakers, unravellers of linear time, unbound by reality and binaries. Monsters being absolved from the laws of reality, however, absolves us for destroying them. The most prevalent monsters of the modern age have been revenges against the ‘successes’ of the West and capitalism. Our movies and stories are full of homogenizing incorporality (from zombies to body snatchers), slashers that haunt suburbia, or the specters that haunt the frontiers of the body, technology, or the unknown. Even if they come back bigger, badder, and grosser, they are dealt with not only to maintain a shaky peace, but to reinforce it. Societies tend to accelerate towards rupture after the appearance of a monster, the breach in safety spiraling into reactionary self-fortification. We all know how monstrous stories end.

Monsters cannot exist without us, however. I mean this quite literally- a world without humans is a world devoid of monstrosity. In my graduate work, I argued that monstrosity (or unfamiliar transformation, to put it simply) not only hinges on humanity, but is a bodily inevitability that exists in each of us. We all hold the kernel of monstrosity, and its germination is beyond our control, as it is in the hands of the society we live in. Think of the monsters of your childhood stories, or, if you’re like me, of the long shadow of American children’s media. The monster is always based on something known, tends to be humanoid or at least bipedal, and often has a human form (or uses one parasitically). That form is either something too-perfect or something white cisheteropatriarchy is quick to cast aside. They are old, poor, disabled (especially if they have facial disfigurements), fat, queer, practice a religion that isn’t Christianity, have dark skin, are not yoked to a nuclear family of their own, the list goes on. These monsters are not only people, they’re me, they’re you, they’re my community, they’re us. Anyone who is in one of these categories likely knows how it feels to have your humanity revoked in intimate and public ways. And as I have skimmed social media these past few weeks, I see my trans siblings in even more danger, I see how the COVID-19 pandemic has created a rise in eugenics. I see the rebirth of 2000s extreme fatphobia and eating disorder culture. I think of the mounting wave of Islamophobia and the texts that went out to black women on the day Trump got elected. When times are hard, the hegemony determines who is on the fringes to be trimmed for the integrity of a nebulous whole. Reactionary self-fortification for a privileged few.

But monstrosity is so easy, so satisfying for a narrative arc without necessary catharsis. The fantastical narratives and villains of the right wing’s multiple millenarian branches (religious or not) have bled into common discourse, and I watch people on the opposite side of the political spectrum pick them up eagerly. They whip up thousands of epithets for Trump and his followers, all of which boil down to ‘fat, stupid, old, bad.’ Sure, it is a delicious little dopamine rush to clown his poorly shade-matched bronzer or call him ‘cartoonish and comically overblown’ (as I have). I would, however, caution us from making synecdoches of their grotesqueries. To call them monsters gives them, bluntly, too much credit. Fascism is an easy route for the insecure, and attributing it to monstrosity does not let us take them seriously, flattens their characters, and, most nefariously, allows us in positions of privilege to skate over any discomfort in the fact that they do represent us. I am acutely aware that white women carried Trump to both terms, and referring to him as monstrous would be an act of self-placating, freeing me of any kinship with him. Monsters are, again, fantastically protean and more powerful than the status quo. Donald Trump is a human man who has skated through life on the immense privilege of his upbringing and has succeeded because our systems are made for people like him to succeed at our expense. The Republican party is so committed to extending its (rapidly diminishing) life expectancy through minority rule that it will kowtow to any strongman, grifter, or zealot with a groundswell. He is the zenith of American systems, not the fantastical aberration.

Our current fascistic zeitgeist also cannot be run by monsters because if there is anything the far right lacks, it is imagination. There are no grand ideas and better futures because all there is room for paranoia and plots, boogeymen that get closer and closer, and life-or-death tests of loyalty. There are only rote tropes in a tightening noose. And in times like this, we must turn to those who observed and critiqued this closing loop before us. I read Eichmann in Jerusalem exactly one year ago after my sister told me to drop everything and pick it up, and within the first few pages it became clear that I was reading a life-defining book, and that Hannah Arendt had graciously provided us with manual for the current unbearable now. The phrase ‘banality of evil’ has been diluted into nothingness in the popular vernacular, but its original application describing Adolf Eichmann’s profound mediocrity and inability to think for himself (but willingness to dilute atrocity through euphemism) is the fascist archetype that we need to remember and hold onto. Little has changed between now and then, as Dorothy Thompson’s 1941 Harper’s Magazine piece ‘Who Goes Nazi?’ sounds eerily contemporary. They wrap themselves in their bombast and posturing, saying that everything is controlled chaos, 5D chess, or is just like their favorite movies. The latter rings the most true- they are predictable in their cruelty, not the best at reading comprehension and nuance, and tragically human in their desires for power and a sense of security. It’s an old, easy pattern for insecure people to fall into, at the cost of the rest of us. And it does not deserve oxygen.

Now is the time of monsters. Now is the time for looking back at history, and for forward action and for imagining a better future. Yes, I am spending half of my days in this bitter interregnum overcome with grief about what we have yet to lose, and the other half preparing and mustering resolve for what we are facing. I’m carving out space for joy and imagination in the face of tariffs, the gloating of the absolute worst people around, and a genuine vein of fear for my community. Working in jobs that put me in direct contact with the alt-right have me wary, and I have felt like Cassandra trying to warn acquaintances and coworkers who are significantly less online (what a gift!) to take their mandates and threats seriously, even if they seem overblown and full of fictional bombast They will easily make monsters of us, and in many cases, already have. Consider this a plea, a warning, a sign, as all monsters are. The old world is dying, and the new one struggles to be born. It has done this many times before. It is humans who struggle against us, not a supernatural threat. Look after the people in your community who are pushed to the edges by the incoming wave, and hold them close at all costs. Because we all know how monstrous stories end.

Books I’d recommend wholeheartedly for the unbearable now:

Eichmann in Jerusalem by Hannah Arendt

The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt

The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein

especially after reading the economic plan for the incoming administration

Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris

Our incoming VP has links to Silicon Valley and the Thiel-set, and Elon has been velcroed to the incoming president’s side. Necessary for any Northern Californian but especially now.

Dark Money by Jane Mayer

Monster Texts I’ve Read and Loved for the Monstrosity-curious

Monster Theory - Reading Culture by Jeffery Jerome Cohen

Our Monstrous (s)kin: Blurring the Boundaries Between Monsters and Humanity ed. Sorcha Ní Fhlainn

Skin Shows by Jack Halberstam